Fixing Retail Electricity Prices

Overview

- Markets are efficient when P = MC

- We discussed two reasons why this might not be the case in electricity generation (wholesale) markets

- Market power

- Externalities

- In this module, we discuss why the retail prices consumers face might not equal social marginal cost:

- Today: timing

- Next class: fixed costs

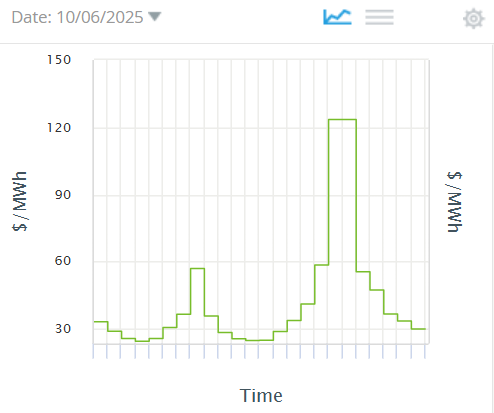

Time varying prices

How it should work

Problem: Most people face a single price

I pay the same price per unit regardless of when I use it.

This is economically inefficient

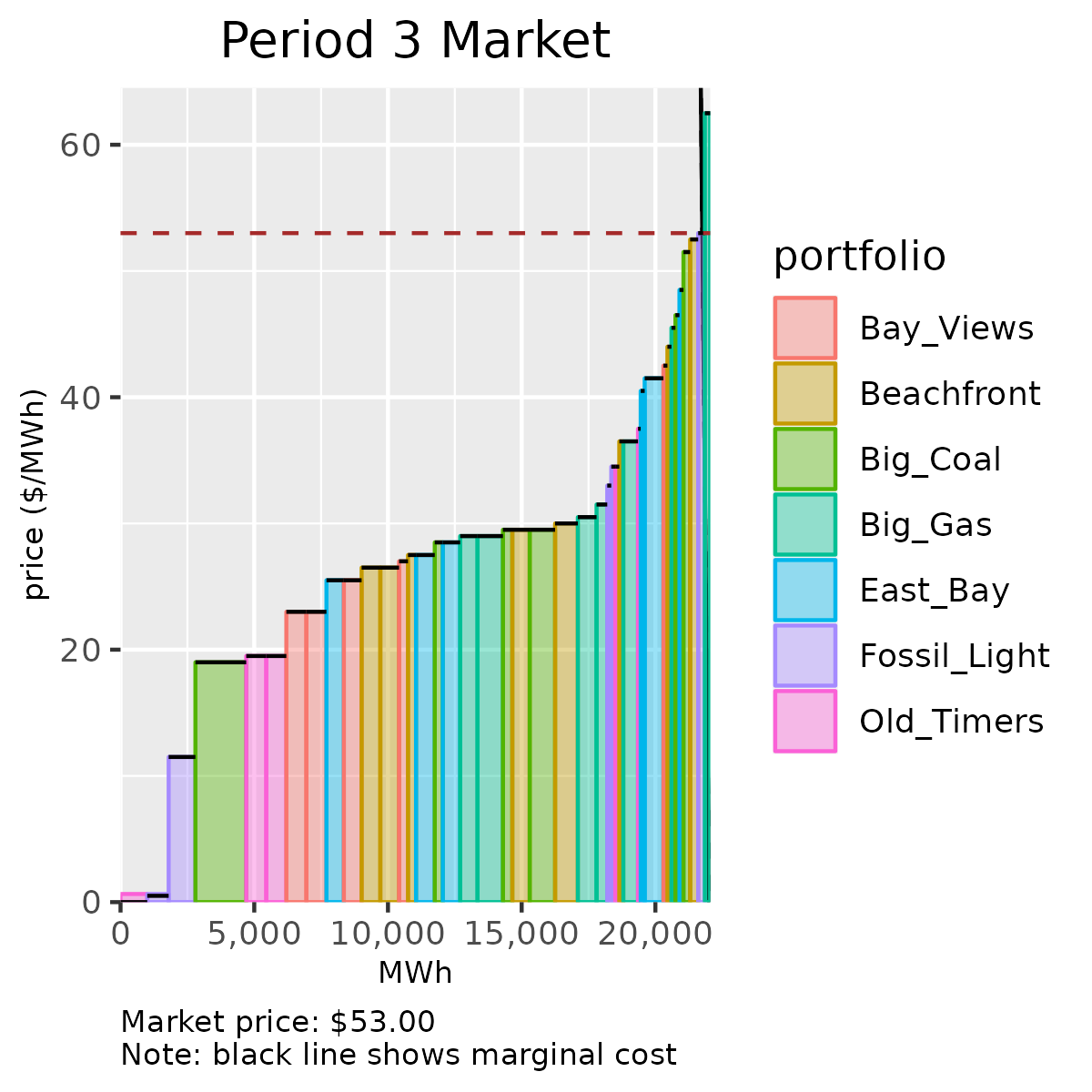

Reminder: Consumption at peak hours is very costly

- some plants only operate a few hours

- if consumers faced these costs during those hours, could we avoid needing some of these “peaker” plants?

- answer depends on how elastic demand really is

If D inelastic, avg price won’t distort Q much

Are consumers really that inelastic?

- Most consumers face a flat price (no sure how responsive they are)

- Some utilities charge higher prices during peak-pricing events … But even then, people don’t change their behavior much

- Is this people’s true preference?

- Think of when you lived off campus? Did you know how much electricity you used?

- If you got a big bill, would you know what to change?

Hypothesis: People are not even aware of how much they use

Jessoe and Rapson (2014)

What is the research question in this paper?

- How much will people conserve if we impose higher prices during peak events?

- Will they respond more if they have real-time information on their electricity use?

Experimental setup

How do the authors go about testing whether people will conserve more if they have more information on their electricity use?

Why is an experiment necessary?

- Real time monitors are available on Amazon

- Could get data on consumers who do and don’t have them installed, and compare their responses to peak price events

- What is the problem with this approach?

How were people recruited?

- To be eligible a customer needed to reside in a townhouse or single family home, have a broadband Internet connection, and sign and return an end-user agreement indemnifying UI against litigation risk.

- Participants offered $40 to complete two surveys

- Emailed 60,000 customers enrolled in paperless billing (likely presence of internet).

- Approximately 7,000 households opened the e-mails.

- Recruited 1,152 households (approximately 1 in 6) to participate in the project

- 437 selected into the final sample.

Sample Groups

Control Group: A total of 207 households were assigned to the control group. These received a mailing that notified them they were in the pilot, informed them of their group assignment, and contained an energy conservation pamphlet documenting “101 Ways to Conserve Electricity.”

Price-Only Treatment Group: The 130 households in this group experienced pricing events that varied in the magnitude of the price increase and the timing of event notification. Two event days:

- Day Ahead (DA): told the day before that price of electricity would be increased by $0.50/kWh (250 percent increase)

- Thirty Minutes (TM): sent notification thirty minutes before a $1.25/ kWh increase

Price + IHD Group: The 100 households get the price treatments above, but also get real-time information on their energy use via in-home display (IHD)

Here are the pricing events

What does the display really tell users?

Customers view in real time the quantity of power being consumed, the price of electricity, and their estimated monthly bill-to-date.

What do we learn relative to the price only group?

Since treatment groups randomly assigned, can see they are the same

We know this isn’t all the \(X\)’s that matter, but if these are “balanced”, we infer that randomization worked.

[Note this paper also has some attrition that they have to deal with.]

JR compare usage across groups on event days

Largest effects were on day 5 and 6

What might be going on there?

With an RCT, can just compare means

- Price-only group usage declines by 0 to 7 percent.

- IHD group usage declines by 8 to 22 percent.

Having established a difference, authors then explore the mechanism

- Doesn’t seem to be “salience” (ie people just more aware an event is happening)

- People seem to plan more for day ahead event (usage changes in hours before / after)

- Some evidence of habit formation. A result they emphasize is that usage declines in non-event hours more among this group as well.

Summary on time varying prices

- Costs vary a lot over time. Economic efficiency demands prices should reflect this.

- How much this will actually effect quantity depends on how elastic demand is.

- Historically, people not aware of what the price is or even how much they are consuming.

- IT changing that.

- Many subsequent experiments have looked at various interventions. My rough take is that a simple programmable thermostat and peak pricing on the worst events gets you most of the social benefits.

Four Fundamental Goals of Rate Design

(from Severin Borenstein)

- Economic Efficiency of Consumption: encouraging additional usage when – and only when – it is valued more than the full additional cost to society

- Cost Recovery: allowing suppliers to recover costs, including the opportunity cost of capital

- Equity: distributing costs among customers in a way that is consistent with societal views of fairness

- Ensuring Access: ensure that everyone is able to consume quantities necessary for basic needs

Recovering fixed costs

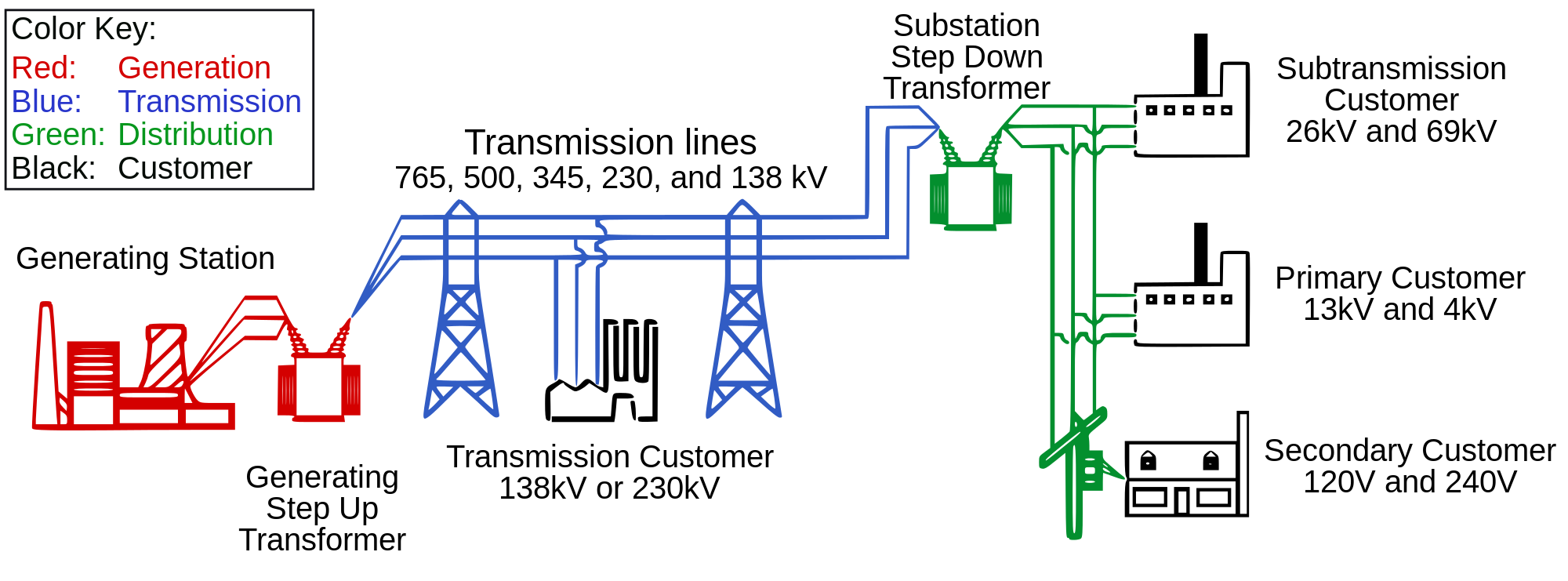

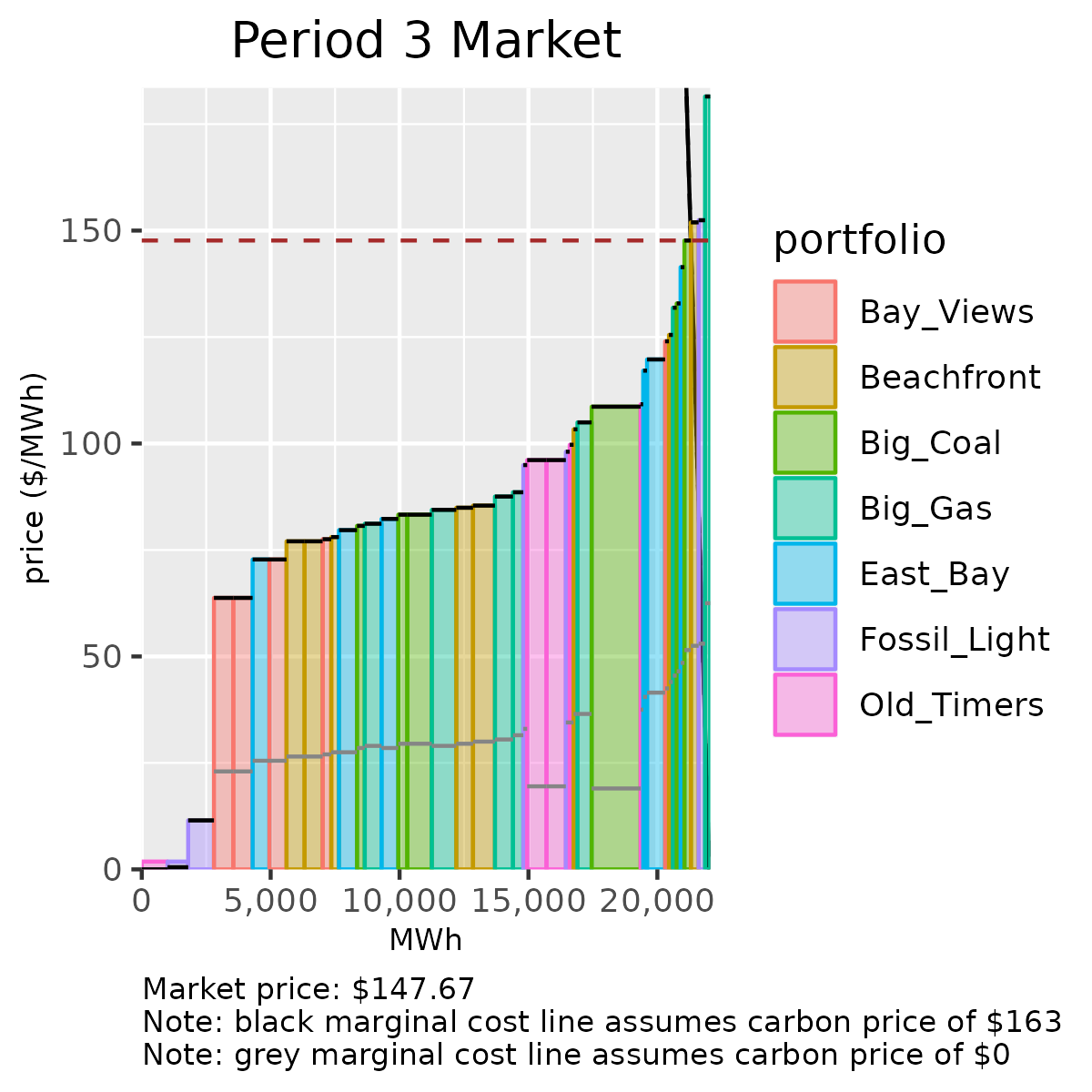

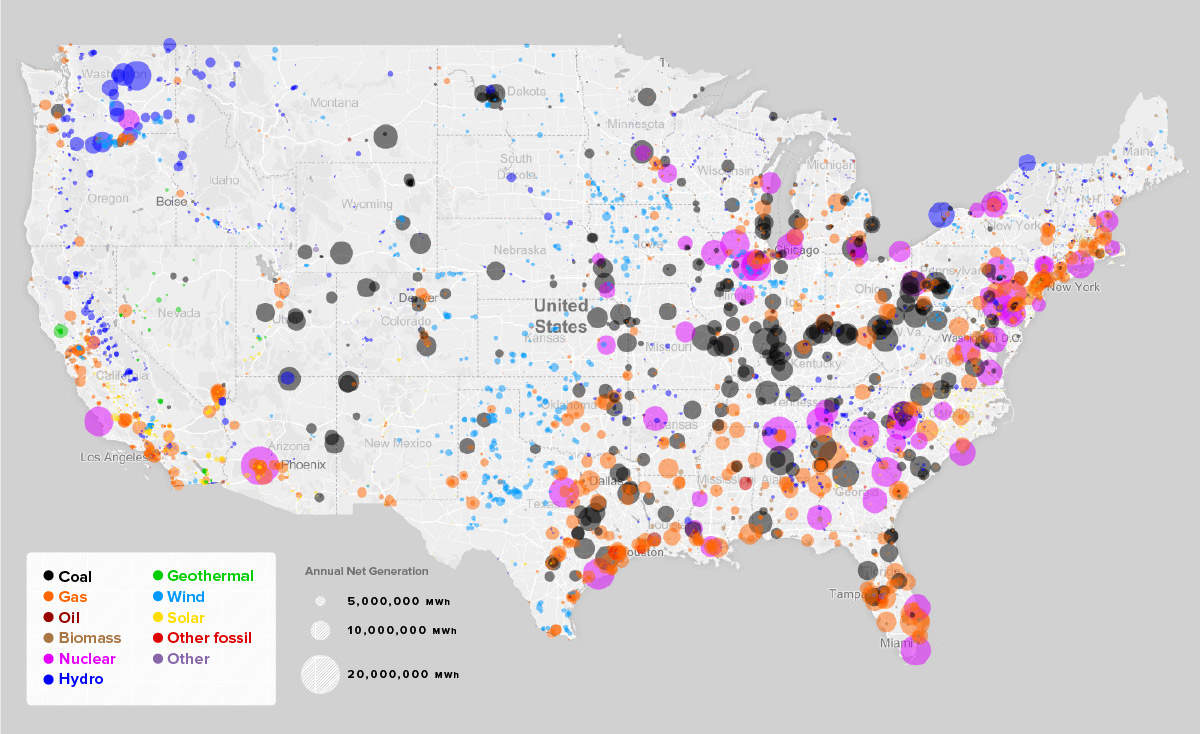

Overview of power system

- What are marginal costs here?

- What are fixed costs?

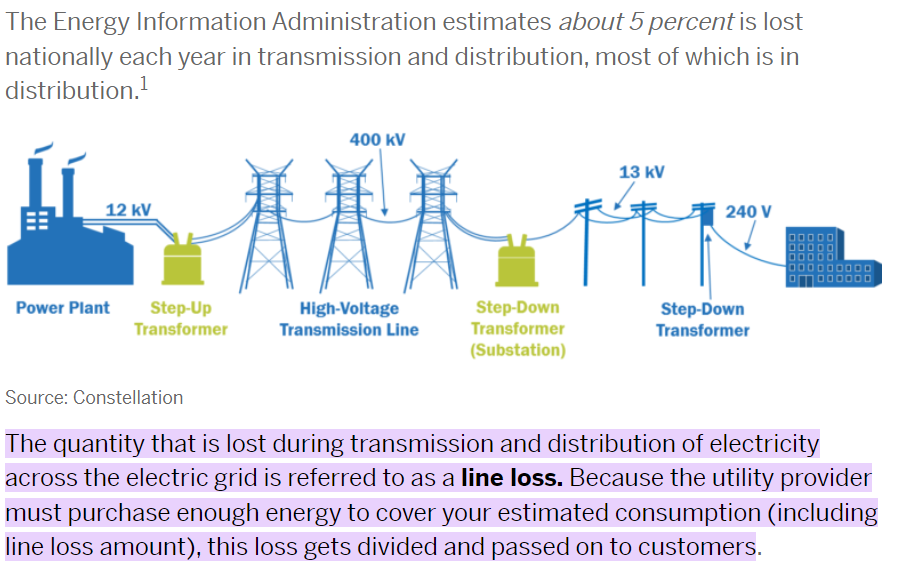

Another cost is line losses

Cost breakdown

Marginal costs:

- cost of production

- line losses

- scarcity cost if constrained (congested)

Basically everything else is a fixed cost.

How should we setup electricity prices and bills to recover these fixed costs?

How much should your utility charge you per kWh?

- Total costs (Q) = Fixed costs + Variable costs(Q)

- Marginal cost = d Variable costs / dQ

- For now, assume MC = constant

- Efficient price = MC

- Problem: If price = MC, utility cannot recover fixed costs.

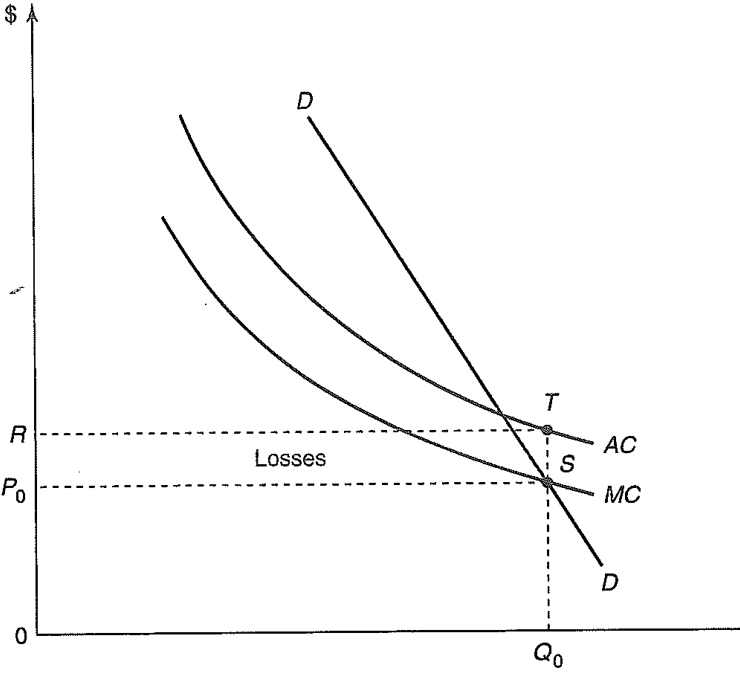

Most utilities recover fixed costs on average

This leads to inefficiently low consumption.

More than half of the marginal price I pay (per unit of electricity consumed) covers non-marginal costs.

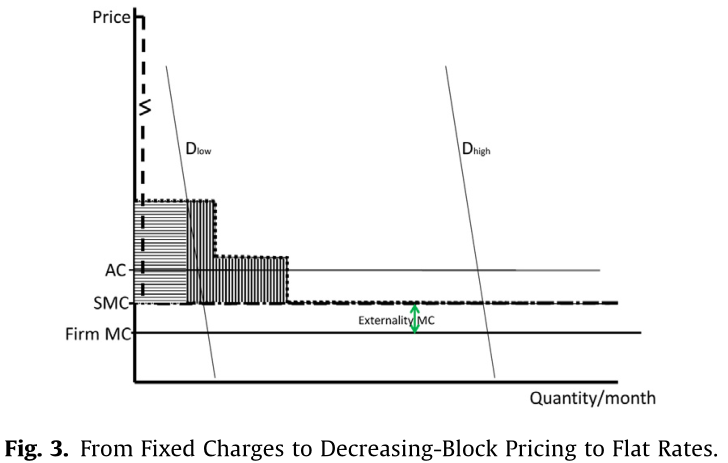

Problem setting Price = AC generates DWL

Average cost = Total costs / Q = Fixed costs / Q + MC

So these are declining in Q (Natural monopoly) Natural monopoly: LRAC declining.

Theoretical best option: Recover fixed costs with fixed charges

- Imagine I had to pay $50 each month just to get any electricity.

- But then only paid the true marginal cost for each kWh.

- That would restore efficiency on the margin, and avoid structural losses.

What are some concerns with this?

Problems with fixed charges

- Some consumers might leave the market

- ie if I get less then $50 surplus (draw this)

- Not equitable

- Why should customers who use very little electricity pay an equal share of the system costs?

- Income concerns, conditional on usage

Fixed charge can be seen as very inefficient price for the first unit

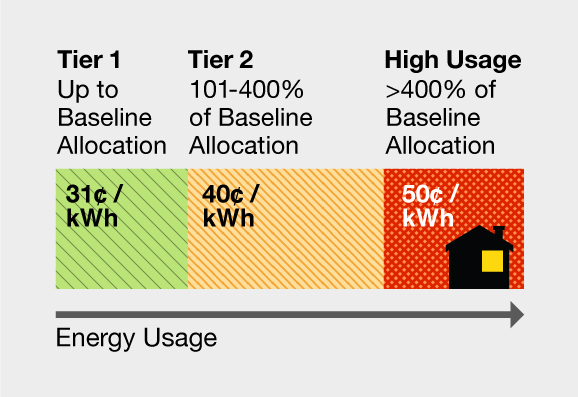

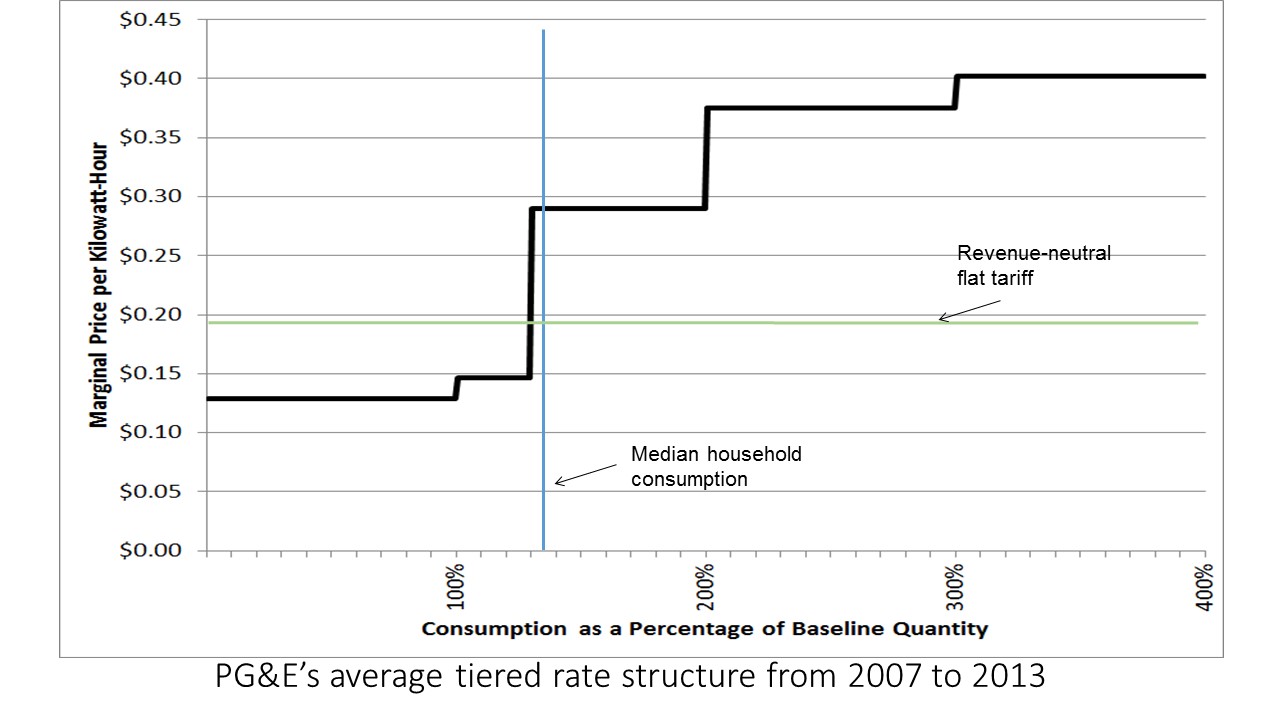

Decreasing block prices rarely observed. But increasing prices often are

Example from SoCal Gas & Electric.

Why do you think some utilities setup prices this way?

Are consumer prices really too high?

- Previous section discussed marginal cost as if it was social marginal cost.

- Electricity production causes large external costs (on the margin) as well.

- Local air pollution: PM, ozone, etc

- Climate change: CO2

- Since these are generally unpriced, simply setting price equal to private marginal cost would mean consumer prices would be too low

What is the net effect? Are prices too low or too high?

Borenstein and Bushnell (2022): Both

B&B look at data from 2014-2016

Summarize wholesale prices at NERC region

Avg wholesale prices much lower than avg retail rates

Avg line losses \(\sim\) 7%; Marginal losses are larger

Estimating external costs

- For each of the four major pollutants from electricity generation (CO2, SO2, NOx, and PM2.5), create a variable that is total emissions damages by hour of the three-year sample for each of the nine regions, incorporating the operations of each fossil fuel power plant and the damages associated with emissions from each plant

- To map local damages to money, use a widely used model (AP3)

- Assume social cost of carbon of $50/ton

- This is way too low now

- Run hourly regressions to translate these average emissions into marginal costs associate with consumption in each utility.

- external MC ~ 2X private MC ..

- but on average prices are too high (\(\sim\) 8%)

- still many places they are far too low

Ramsey pricing

If we must recover fixed costs volumetrically (on the margin), how should we do it?

Should different consumers pay different prices?

When we will the deadweight loss from pricing above MC be largest?

- consider two different groups of consumers

- one has very inelastic demand, the other very elastic demand

- could be residential vs commercial, rural vs urban, rich vs poor, etc

- which group generates more DWL?

Solution: Ramsey pricing

If you must raise revenue from marginal pricing, its efficient to target the most inelastic consumers

What groups of consumers do you think are most inelastic?

- What type of households?

- Businesses vs residential?

- This is why commercial and industrial consumers often get lower marginal rates: They argue that they will move their business elsewhere.

- What do people think about this?

Residential rates exceed Com and Ind

Summary on fixed cost recovery

- Electric power consumption relies on a complex system of generation, transmission, and distribution. Many of these costs are fixed.

- Recovering fixed costs through marginal pricing leads to inefficiently low consumption.

- Fixed consumer charges and, to a lesser extent, Ramsey pricing can help reduce the losses, but each has problems.

- Might hope that this sort of offsets missing externality prices … but empirical evidence suggests in many places the prices are too high.

Utility Regulation

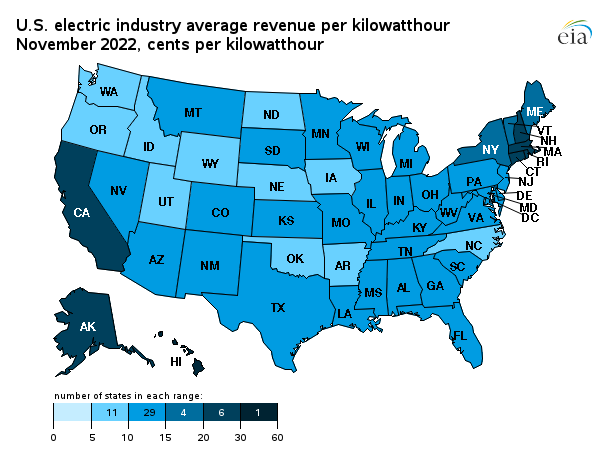

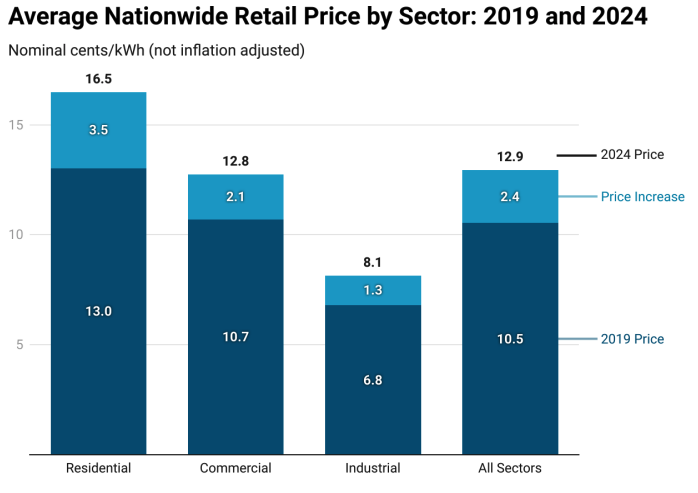

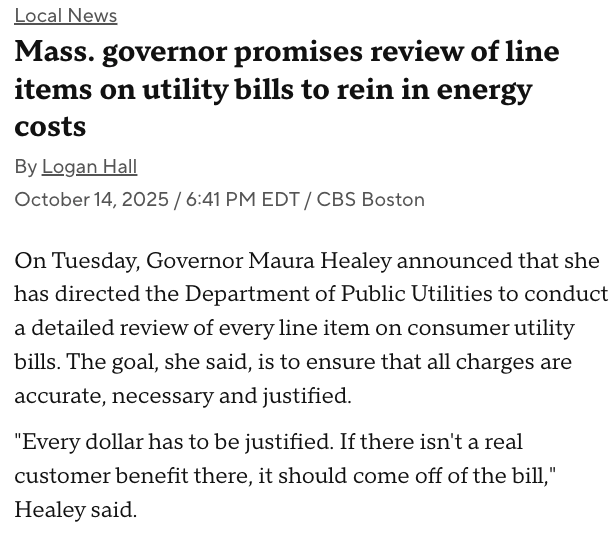

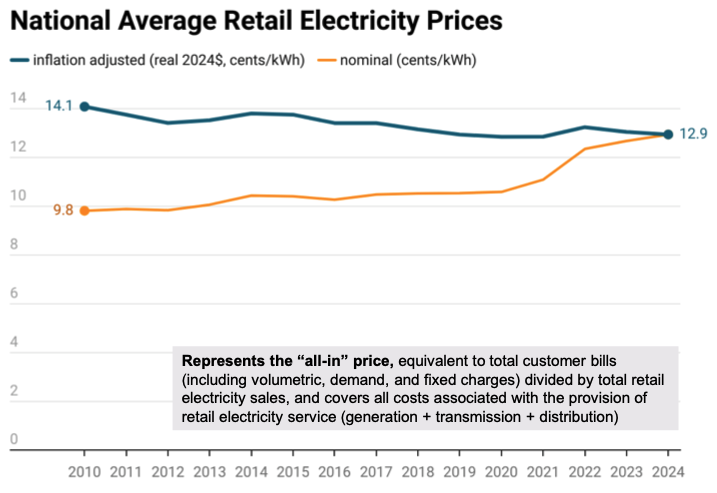

Electricity price increase all over news lately

Important context

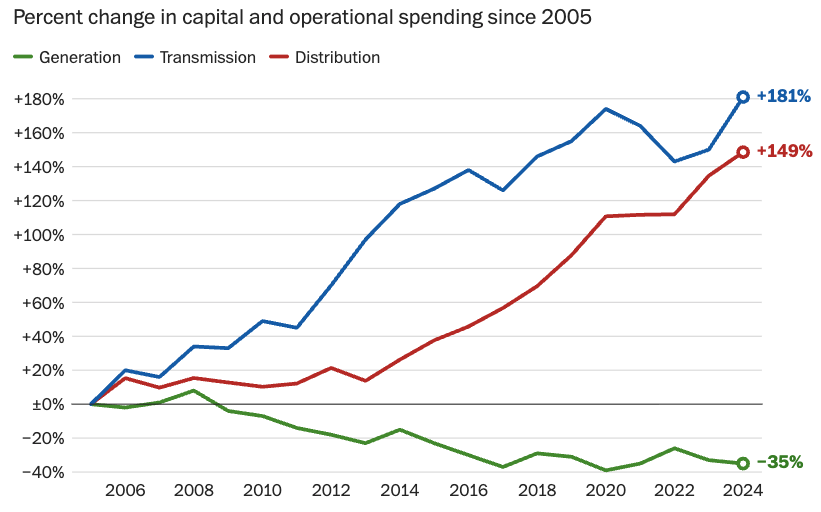

But something defintely going on with T&D costs

Whats going on here?

- Many new investments needed:

- Wildfires

- Extreme weather

- Aging infrastructure

- EVs

- All of these are driving up fixed costs

But also, “utility regulation sucks” (Heatmap)

Traditional Utility Regulation

Industry thought to be a natural monopoly

What makes a natural monopoly?

- Declining long run average costs (LRAC)

- the more you produce, the lower your average cost

- What generates this?

- Large fixed costs

- Economies of scale

- Implication: (theoretically) cheaper to produce with a single firm

How to fix the monopoly pricing problem?

- Natural monopoly: a single firm can produce cheaper than many firms

- However, a single firm also has the ability to exert market power, undermining these cost efficiencies

How should the government balance the cost savings and market power concerns?

- One option is to have the government simply run operations

- ie USPS

In US electricity, a “regulation” system was preferred

- Regulation typically done at the state level.

- Monopoly utilities would make investments in generation and supply power

- The regulator would set price they could charge such that they earned a “fair” return on these investments

Goals for the electric power system

- Keep the lights on! (avoid blackouts)

- At the lowest possible cost (or price?)

Traditional rate-of-return regulation:

The regulator allows firm to collect just enough money:

- cover “prudent” costs

- earn a “fair” return invested capital

\(\text{Revenue Requirement} = \text{O&M} + \text{Energy} + r \times \text{Rate Base}\)

- operations & maintenance (labor, trucks, repairs)

- Fuel = cost of energy inputs (ie wholesale purchases)

- Rate Base = undepreciated capital invested

- \(r\) = allowed rate of return (set by regulator)

The “rate case”

What the utility brings to the regulator:

- Its Regulatory Asset Base (“rate base”): poles, wires, substations, meters, transformers, etc.

- Its expected O&M: salaries for lineworkers, truck fleets, tree trimming, call centers.

- Its expected purchased power costs.

- A proposed “reasonable” rate of return (r) on capital.

The “rate case” (.cont)

What the regulator decides:

- Which costs are “prudently incurred.”

- Which assets are “used and useful.”

- What the allowed (r) should be (often tied to the utility’s cost of capital).

Output of the rate case:

An approved Revenue Requirement for the year.

From Tariff Design to Customer Bills

- Turn Revenue Requirement into specific charges:

- fixed monthly charge,

- ¢/kWh usage charge,

- Customers are billed using that tariff.

- Actual dollars collected from customers = actual usage × approved rates.

- If actual ≠ forecast, rates adjusted next time.

- Implication: utility essentially guaranteed to recover approved return on investment. (no more, no less)

What are some concerns with this system?

(ie why does utility regulation “suck”?)

- 1. Provides no incentive to minimize operating costs

- 2. Biases firms towards accumulating capital

How profit works for an unregulated firm

- Sets price to maximize profit

\(\pi = P(Q)\cdot Q - C(Q)\) - Keeps all gains from lowering cost.

Incentive:

- Automate / Streamline

- Lean staffing / cheaper inputs

- Constant pressure to minimize total cost

→ Lower cost → higher profit per unit.

In contrast, a regulated utility has no incentive to be efficient

\[\text{Revenue Requirement} = \text{O&M} + \text{Energy} + r \times \text{Rate Base}\]

- Under regulation, price is guaranteed to cover costs.

- If they do a bad job, consumers foot the bill.

- If they do a good job, regulator takes the savings and gives it to customers.

- This gives regulated firms no incentive to reduce costs

Problem 2: Capital bias

- The utility “makes money” (earns a return) on capital it has invested in physical assets

- (poles, lines, transformers, underground cables, smart meters, etc.).

- But it does not earn that same allowed return on variable costs (O&M).

- (maintenance labor, tree trimming, routine repairs, customer service, etc.).

- These costs are simply passed through to customers with no return.

This tilts decisions toward capital-intensive solutions.

Example: maintenance vs. upgrade

- Option A: keep old wooden poles

- Annual maintenance crew cost: $10M/year (O&M).

- Option B: replace with new composite poles & hardware

- One-time capital spend: $200M.

- Maintenance falls to $3M/year for 20 years.

- That $200M goes into the rate base.

- If allowed return r = 8%:

- The annual revenue requirement goes up by ~$11 million per year!

- ($18M increase minus $7M O&M decrease)

- The annual revenue requirement goes up by ~$11 million per year!

- Utility earns money on B but not A.

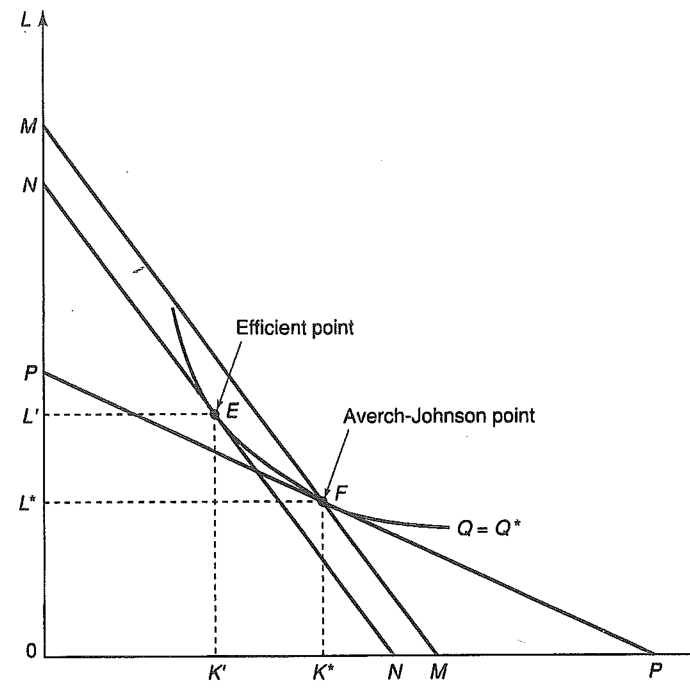

Capital Bias (Theory) - Averch–Johnson effect

In a normal market, inputs are selected to minimize the cost of achieving any output

- Revenue produced by combining capital and labor \[\pi=R(K,L)-wL-rK\]

- Ratio of first order condition for both inputs yields: \[\frac{\partial R/\partial K}{\partial R/\partial L}=\frac{r}{w}\]

- Inputs are selected such that the ratio of marginal products is equal to the ratio of marginal costs

Rate of return regulation distorts input choices

Max profits subject to the constrained return on capital \[\begin{aligned} \pi & = R(K,L)-wL-rK\\ \text{s.t. } & \frac{R(K,L)-wL}{K} = s \end{aligned}\]

This effectively distorts relative prices \[\frac{\partial R/\partial K}{\partial R/\partial L}=\frac{r-\alpha}{w}\]

- where \(\alpha=\frac{\lambda(s-r)}{l-\lambda}>0\)

Since we know the market input mix was efficient, this has to come at a social cost

- regulation effectively subsidizes building stuff

The Averch-Johnson Effect

Source: VHV ch 12

Regulation Summary

- Electric power historically run as vertically integrated regulated monopoly.

- The primary objective of this system was to keep the lights on, and it did that quite well.

- But perverse incentives distorted behavior:

- Because costs were covered, the utility had no incentive to operation efficiently.

- Because returns were tied to capital expenditures, utilities were distorted towards building large expensive plants.

Recent trends bringing issues back to forefront

- The energy transition will require a lot of investment

- Smart grid, renewables, storage, EV infrastructure, etc.

- How do we know what’s really needed and where?

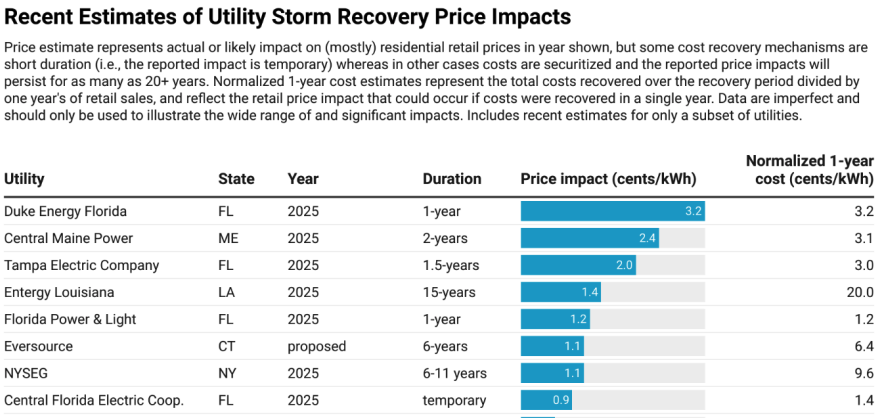

- Extreme weather events destroys infrastructure

- Utilities want to rebuild stronger. Is it worth it?

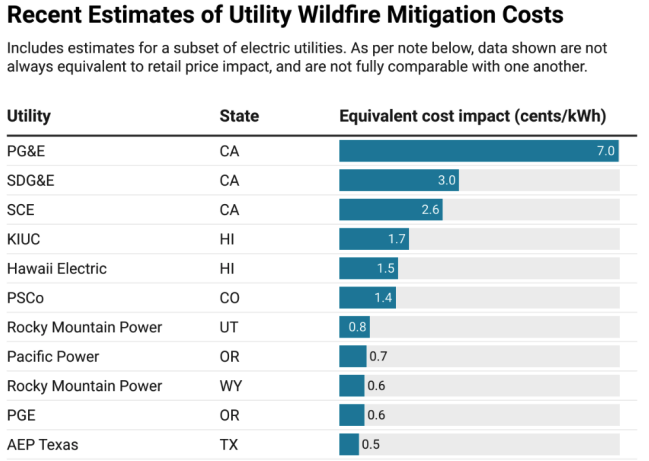

- Wildfire mitigation is essential

- Should we put lines underground? Or trim trees?

- AI boom…

- See this LBL report for details

Distributed Solar Power and Retail Pricing

What happens when consumers can produce their own electricity?

- To combat climate change, need to transition to renewables asap

- Solar will probably be the dominant source of electrictiy generation in the future

- A large share of this solar is actually distributed on rooftops of homes and businesses

- This decision depends on utility rates and also affects utility rates going forward.

Grid scale vs distributed solar

What are some pros and cons of distributed relative to grid scale?

Pros of distributed generation

- No line losses (7-9%)

- Cheap real estate

- your roof is unused space anyways (may even provide shade)

- May reduce need for new transmission /distribution lines

- Spreading panels around reduces ‘risk’ of clouds

- “Freedom” / independence from the grid etc

- strange coalition of environmentalists and anti-government types has emerged to support PV

Cons of distributed generation

- Design and maintenance is MUCH more expensive

- Lose all economies of scale

- GS panels often move throughout the day to track sun

- DG installed where consumers choose, not grid operators

- Also a lot of controversy over the true cost of DG and how it should be promoted

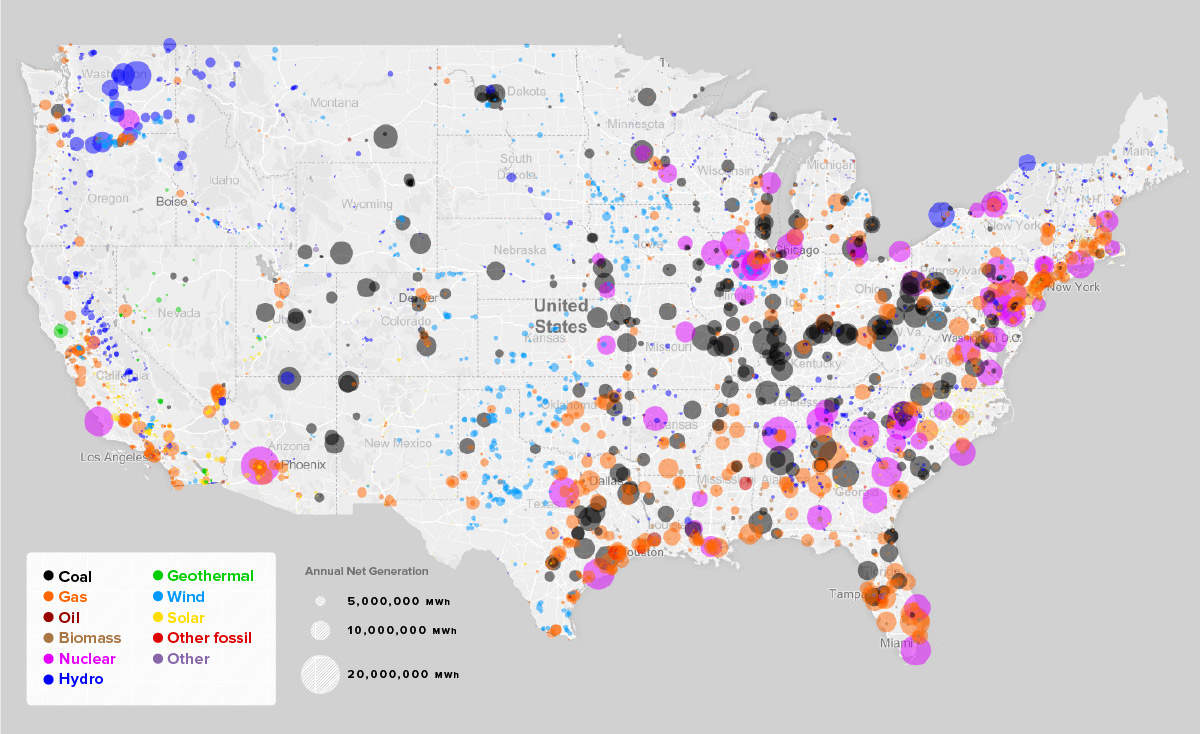

Where should we put solar?

If you were a social planner, where would you put solar panels? and Why?

- Sunny places (low LCOE)

- High demand places (high value)

- Places with lots of polluting plants

Where will solar actually be installed if it’s up to individual consumers?

What factors will make some consumers more likely to install solar panels than others?

- High (marginal) electricity prices

- Subsidies

- Environmental preferences

The private economics of solar PV adoption

- Consumers have utility from electricity consumption \[U=\sum_{h}(u_{h}-p_{h})e_{h}\]

- \(u\),\(p\),\(e\) represent utility and electricity consumption in hour \(h\)

- most consumers face a flat price for electricity (\(p=p\))

Installing solar panels reduces the need to buy electricity from the grid by the output of the panels (\(s\)).

\[U_{s}=\sum_{h}(u_{h}e_{h})-\sum_{h}p(e_h - s_h) +\omega-F\]

- \(\omega\) represents the “green glow” of going solar and \(F\) is the fixed cost of the installation.

- Ignore discounting for now.

- Then it makes sense to adopt if: \(\sum s_{h}p+\omega>F\)

Who adopts in this model?

Adopt if, \(\sum s_{h}p+\omega>F\)

- consumers with high \(p\) and \(s\)

- if can’t sell back, consumers with high usage too

- “environmentally conscious” consumers (high \(\omega\) )

- consumers that face low fixed costs (\(F\))

- possibly due to subsidies

- These factors explain the patterns in following map.

- They also reflect policy options

What put California at the top of residential solar?

CA has increasing block pricing

Goal: Recover fixed costs equitably.

Result: Large consumers size system to get on low tier.

Source: Severin Borenstein

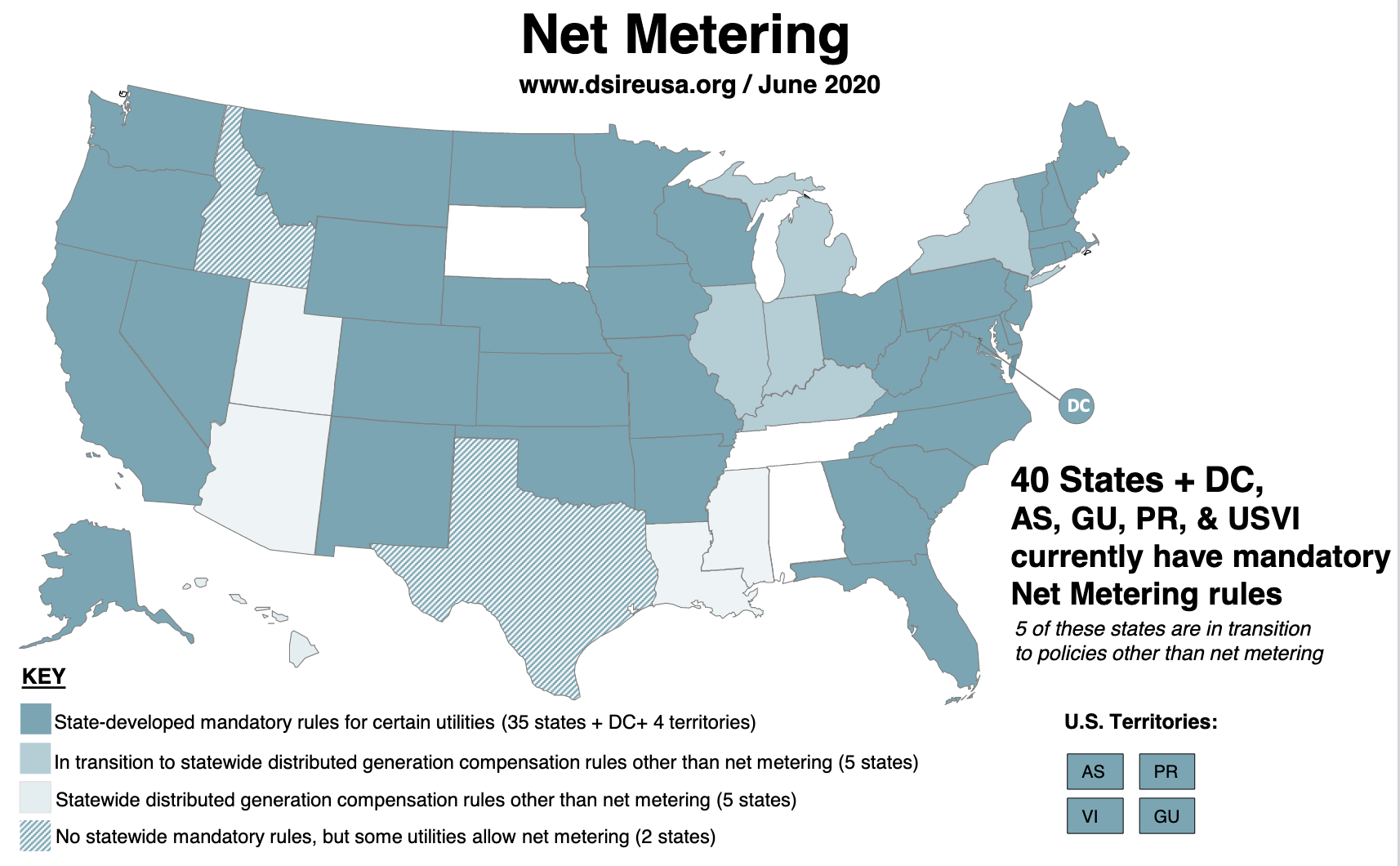

What if you produce more than you consume?

Common policy: net energy metering (NEM)

- NEM allows PV owners to sell power back to the grid

- This breaks the temporal cap on solar (\(s_{h}<e_{h}\))

- Most places in the US still require \(\sum_{h}s_{h}<\sum_{h}e_{h}\)

44 states currently allow net metering

When customers sell solar back to the grid, what price should they receive?

- In the bill we looked at, I paid $0.217/kWh

- If I reduce consumption by 1 kWh, I save $0.217

- If I sell power back to the grid, what price should I receive?

Solar production and consumption generally not aligned

Wholesale cost avoided varies over time

In CA we often have too much solar mid-day

- The price in these periods can actually be negative!

The price on your bill includes fixed costs

- I paid $0.217/kWh, but only half of that was for generation.

- Fixed charges \(\approx\) total system cost independent of quantity consumed, divided by anticipated sales.

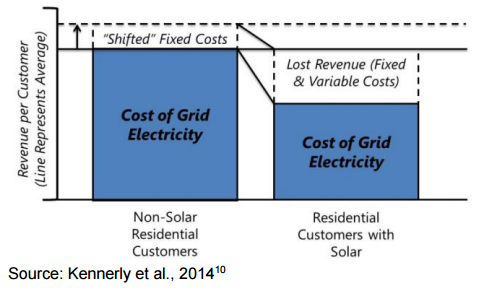

Major problem

As PV owners buy less electricity, the burden of those fixed costs will be shifted onto other households

- That increase in prices will incentivize even more households to install PV…..

- This is the utility “death spiral”

One solution is to charge consumers a large fixed cost just for being connected to the grid

- What do people think about this?

So what’s the answer?

How should we compensate / encourage solar PV?

- efficient solution would

- charge a fixed fee for everyone that uses (or may use) the grid

- incentivize people to reduce consumption at times when it is more valuable

- but that value is the wholesale price

- pricing externalities makes subsidizing solar irrelevant

Summary on Solar

- Solar value proposition closely related to subsidies, sun, and the price you pay for electricity.

- Subsidies have been generous, not obviously correlated with social value, and very volatile.

- Letting people sell back to the grid makes sense, but at what price?

- When large parts of the population install solar, we need to rethink how we cover the fixed costs of a reliable power system.

Econ 3391 - Retail Prices